|

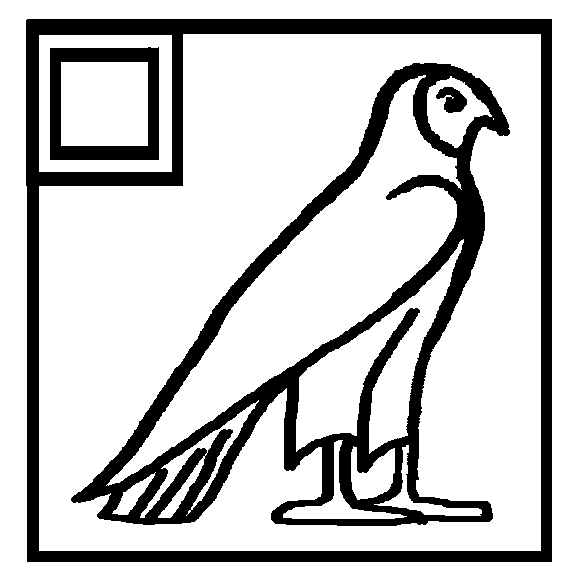

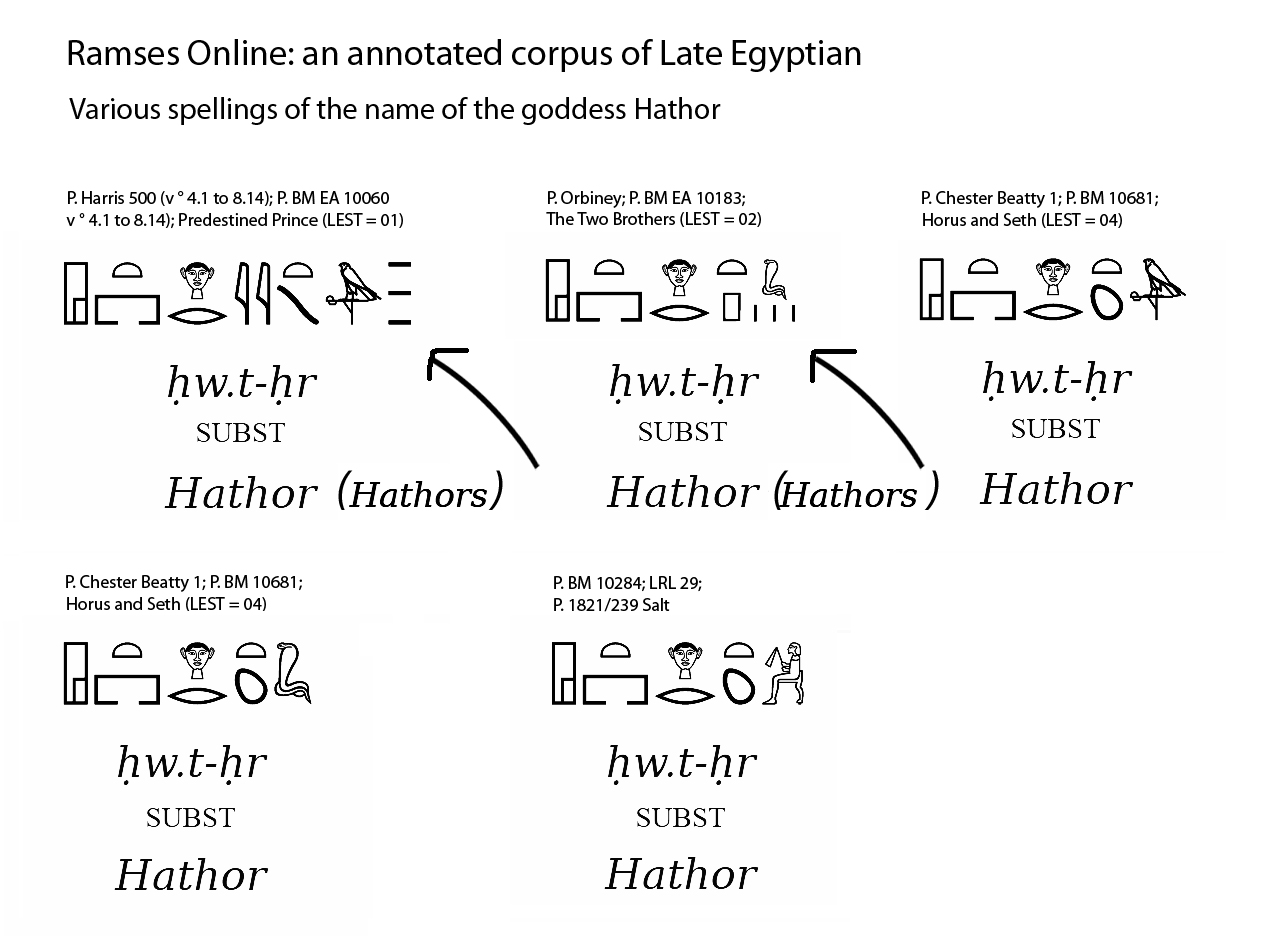

The glyph above is the most frequent way to name Hathor, but there are others. Via SAOC 55, _For His Ka: Essays Offered in Memory of Klaus Baer_. I learned of another way in which Hathor might be referred to:

The phonetic spelling of Hathor (Footnote 42, page 27, see below.)

Notice, each of the variations above share a glyph, "O6", "hwt":

Furthermore, the goddesses Nebthet (Nephthys) and Hathor (Hethert) share that hieroglyph!

"The seven Hathors appear at the birth of a child and predict the fate of the newly-born. In the famous story of 'the prince and the destiny' they prophesy that the prince shall meet his death through a crocodile, a serpent or a dog. This prophesy, however, does not imply an inevitable fate, but rather designates three evil chances which can perhaps be avoided. The end of the story is missing, but presumably they are avoided because of the prince's courage, his trust in [the Gods} and the love and care of his wife." (From _Hathor and Thoth: Two Key Figures of the Ancient Egyptian Religion_, by Claas Jouco Bleeker, pages 71-72) The first example is from this story, I did read all the way to the end, because I was curious which got the prince, and no one knows now. I'll go with Bleeker's optimistic view, though. The second example is from the Orbiney papyrus at the British museum, EA 10183; The Two Brothers. I didn't read all of it, but learned that the story ends happily, with the brothers Bata and Anpu "at peace with one another and in control of their country". The next two examples are from the Papyrus Chester Beatty, and the last is from the Salt papyrus, all four papyri are at the British Museum. And now to the traces...

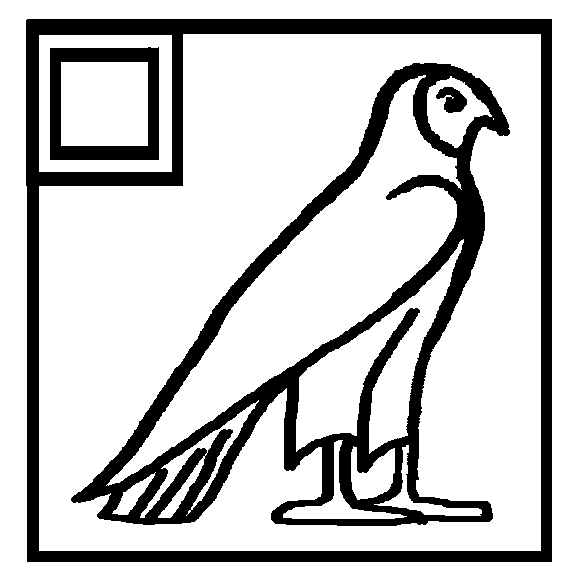

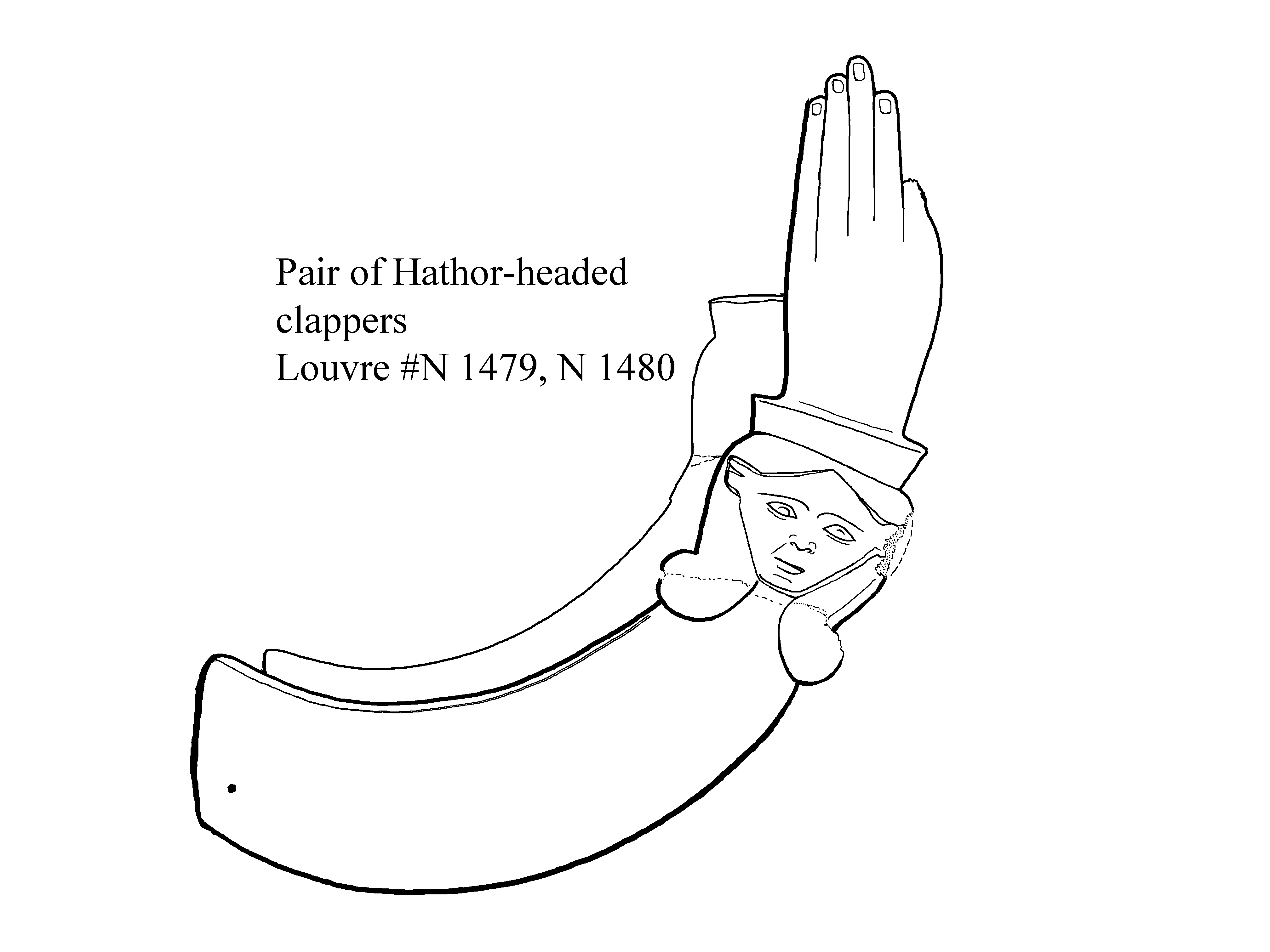

Pair of clappers with the head of the goddess Hathor Middle or New Kingdom? 2033 - 1069 BCE Ivory from hippopotomus teeth, Height: 35,40 cm.; Length: 7,40 cm. Louvre, # N 1479, N 1480 Traced from a photo by Heidi Kontkanon Andrea "Amberinsea" has a view of the front side of the other clapper I'm finding the imagery for the goddess Hathor rich and varied. These two clappers are curved, due to the shape of the hippopotamus ivory with which they were carved. Each end was originally decorated with the head of the goddess Hathor and a slender hand, although the one clapper has since lost its hand. In antiquity they would have been held together by a cord inserted through a tiny hole each has at the end. They would have been used as a percussion instrument by clapping them together. Clappers like these "seem to be the first musical instruments to have been depicted on vases, as early in the predynastic period. Clappers with hands appeared in the Middle Kingdom, yet it seems that the most beautiful of these objects can be dated to the New Kingdom, particularly those representing a head of Hathor. Music and dance played an important role in ancient Egypt..." (From the museum website) Bleeker quotes an excerpt from a "song sung by the seven Hathors to the great goddess Hathor":

"We laud thee with delightful songs,

(Printable version).

The Cairo museum has two examples of clappers:

"Although the respective sister pieces of these two isolated clappers are lost, they nevertheless serve to illustrate characteristic types from among the many and varied examples known. The clapper with the broken handle shows a fairly well modelled woman's head surmounted by a right hand complete with fingernails. The other takes the form of a bent arm at the end of which a Hathor head with cow's ears, curled wig and bead collar supports a structure flanked by two horns. A tapering left hand, adorned at the wrist with two incised bracelets, elegantly extends the curve of the arm. The hole pierced through the bottom of this arm shows that the clappers were originally attached by means of a string."

"Priests and priestesses of Hathor owned these instruments and used them to keep rhythm at dances performed in the goddess' honor. In some rare examples, the head of a woman replaces that of Hathor." But perhaps, even though the woman is not wearing the cow's ears or the usual headdress of Hathor, this head still represents Hathor?

Quotes are from, and photo adapted from the one in, _Official Catalogue: THE EGYPTIAN MUSEUM CAIRO_, edited by Mohammed Saleh and Hourig Sourouzian, photographs Jüergen Liepe, translated by Peter Der Manuelian and Helen Jacquet-Gordon, © 1987 Verlag Philipp von Zabern, Mainz.

The Phoebe Apperson Hearst Museum of Anthropology has a broken clapper, but the part that remains has exquisite detailing. Hathor wears an elaborate collar, and the sistrum area has been elaborated with uraei.

The Quest for Immortality: Treasures of Ancient Egypt by Betsy Morrell Bryan and Erik Hornung gives "Luxor Museum J 136" as the museum source, BUT since 2002, when that book was published, a new museum has been established in Kom Ombo, simply called the "Crocodile Museum". The front view of the cube has a Hathor sistrum and below that, a rebus which means "Beloved of Nebmaatre" (Amenhotep III). On another side, Nebnefer is "Kissing the earth for Hathor. I have given you adoration to the height of heaven, while I cause your hearts to be satisfied every day, by the priest, royal scribe and divine sealer of Amun, Nebnefer.' Beneath this is a horizontal band of hieroglyphs: 'Made by the priest of Amun, Nebnefer'."(QfI, page 185)

There are six of these capitals in museums, plus several sad fragments still extant in the Bubastis open air museum. I've found, besides the one at MFA which I've seen and snapped, capitals at the British Museum, the Louvre and the Australian Nicholson museum. In _The Encyclopedia of Ancient Egyptian Architective_ Dieter Arnold gives the museum and accession numbers of two more Bubastis Hathor capitals, Berlin's Ägyptisches Museum #10834; and Cairo's JE 72134, in the museum's gardens. By referencing many different photos of these pieces, I've come up with this composite drawing. The capital at the Nicholson museum might not have had a row of uraei, the break is a very clean one. But the other three show seven uraei from the front view and the Louvre example shows five uraei from the side view, along with a papyrus scepter at the center and two crowned uraei on each side of the scepter, such that these two show from the front view. I opted not to include these side uraei in my trace. It's uncertain if the capital at the Nicholson museum had them originally. The curving side lines probably represent the curved lines in the sistrum as in Nebnefer's block. Nebnefer's cube is clearly from the 18th Dynasty, in the time of Amenhotep (Amenophis) III's reign (1390-1352 BCE), as it contains a rebus, "Beloved of Nebmaatre". Edouard Naville, who excavated the Bubastis columns in 1887-1888, thought these also did, even though today credit is given to Osorkon of Dynasty 22, reign of Osorkon, (874–712 BCE). Osorkon, like so many before him, might have simply usurped them. "Besides, it cannot be denied that the Hathor capital with two faces of the goddess is met with in temples of the eighteenth dynasty, at Deir el Bahari, where it dates probably from Hashepsu or Thothmes III., at El Kab and Sedeinga, where it dates from Amenophis III. In the last two instances there is another similarity with the Hathors of Bubastis, the two sides which have not the face of the goddess bear the emblematic plants of North and South. Under such circumstances it may well be asked whether the colonnade of Bubastis is not the work of the eighteenth dynasty, and of Amenophis III, whose name is preserved on several statues discovered in the excavations." (Edouard Naville, Bubastis: Eighth Memoir of The Egypt Exploration Fund, (London, Gilbert and Rivington 1891), page 13) I'm inclined to agree with Naville. The mouths have that distinctive full Amenhotep look!

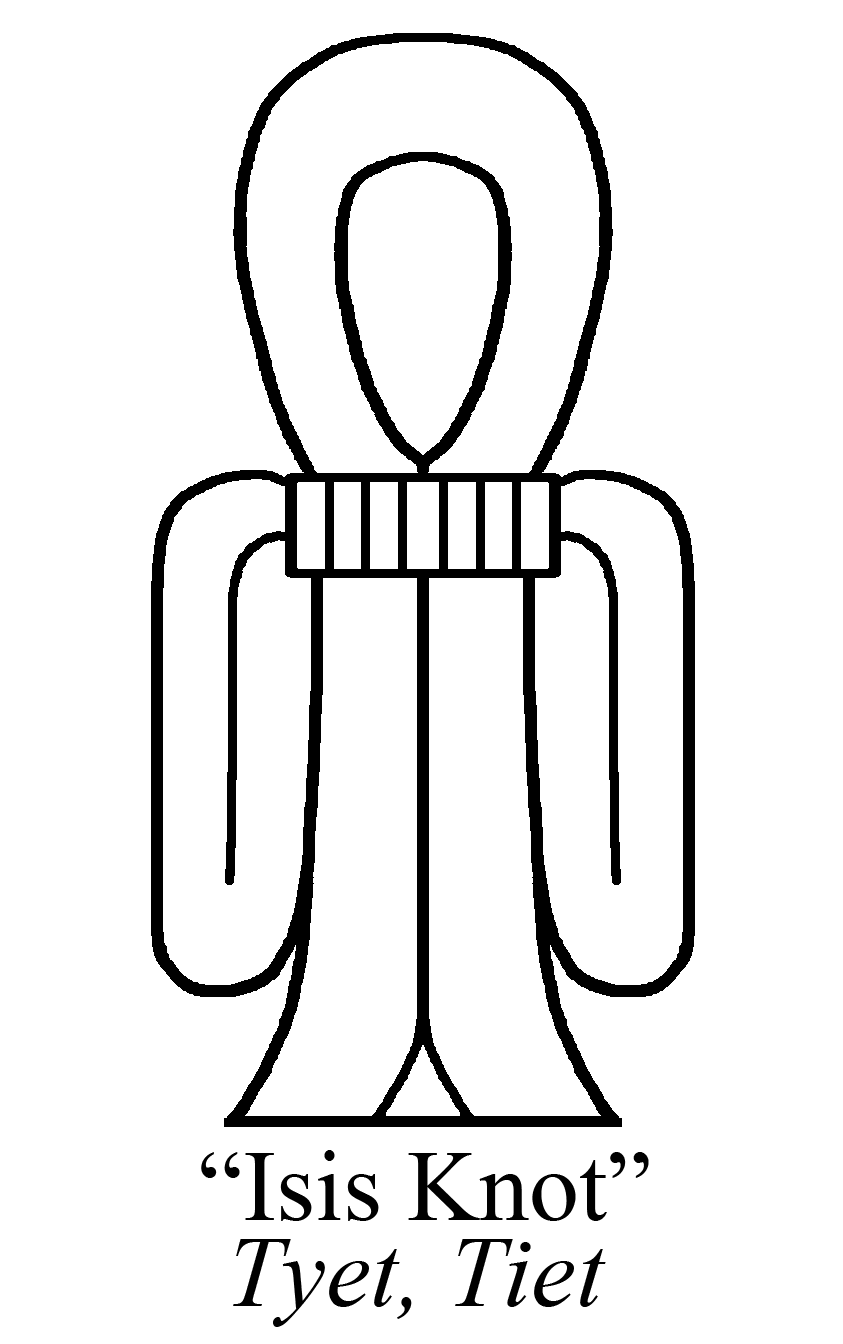

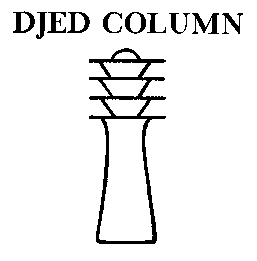

This piece is so fascinating because it's combining various symbols. We see the Tyet amulet's "arms", and the "spine" (connoting stability) of the Djed pillar:

Djed From _Reading Egyptian Art_, Wilkinson I've seen various guesses at the meaning of the Tyet. Often associated with the goddess Isis (Aset), it suggests protection and health.

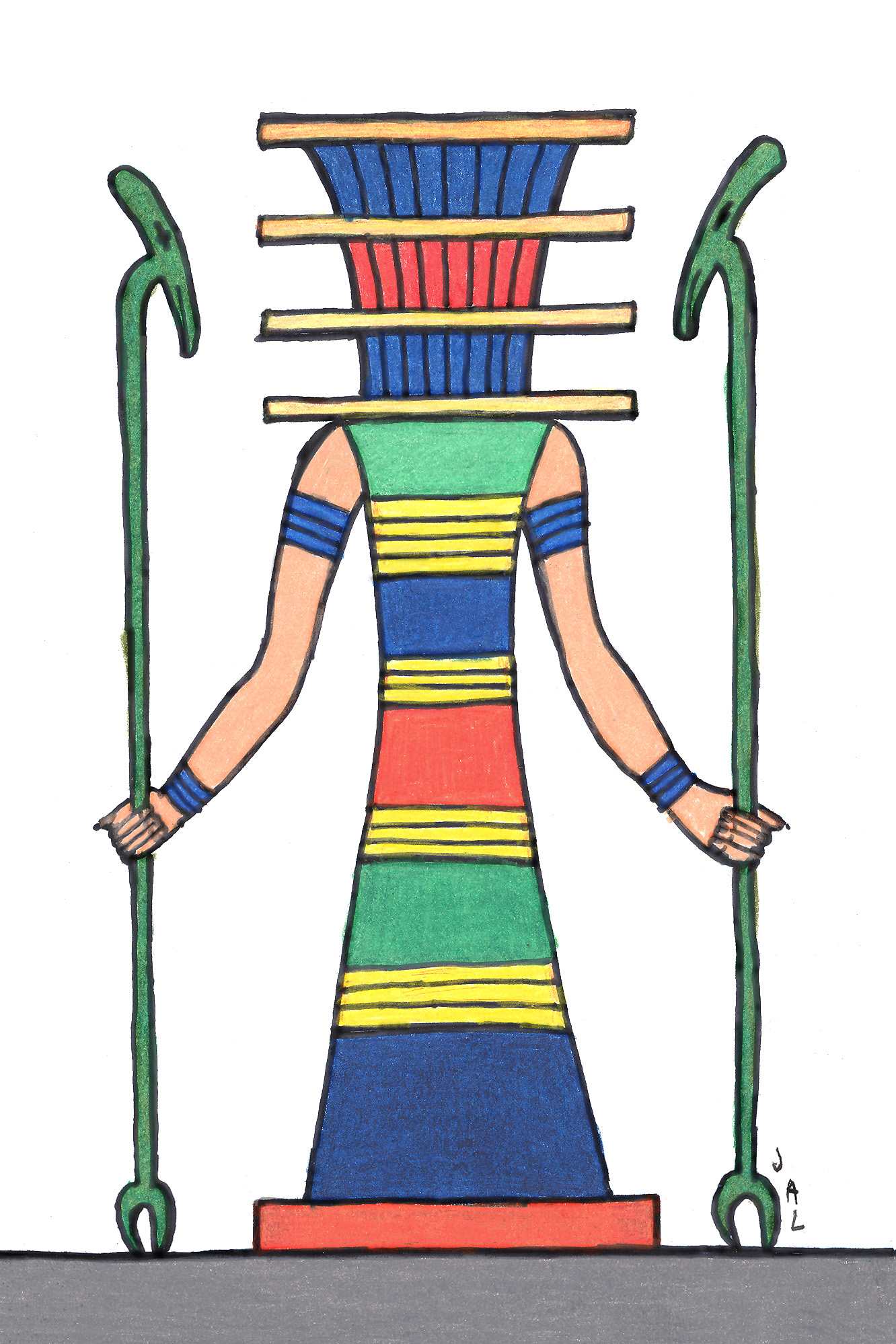

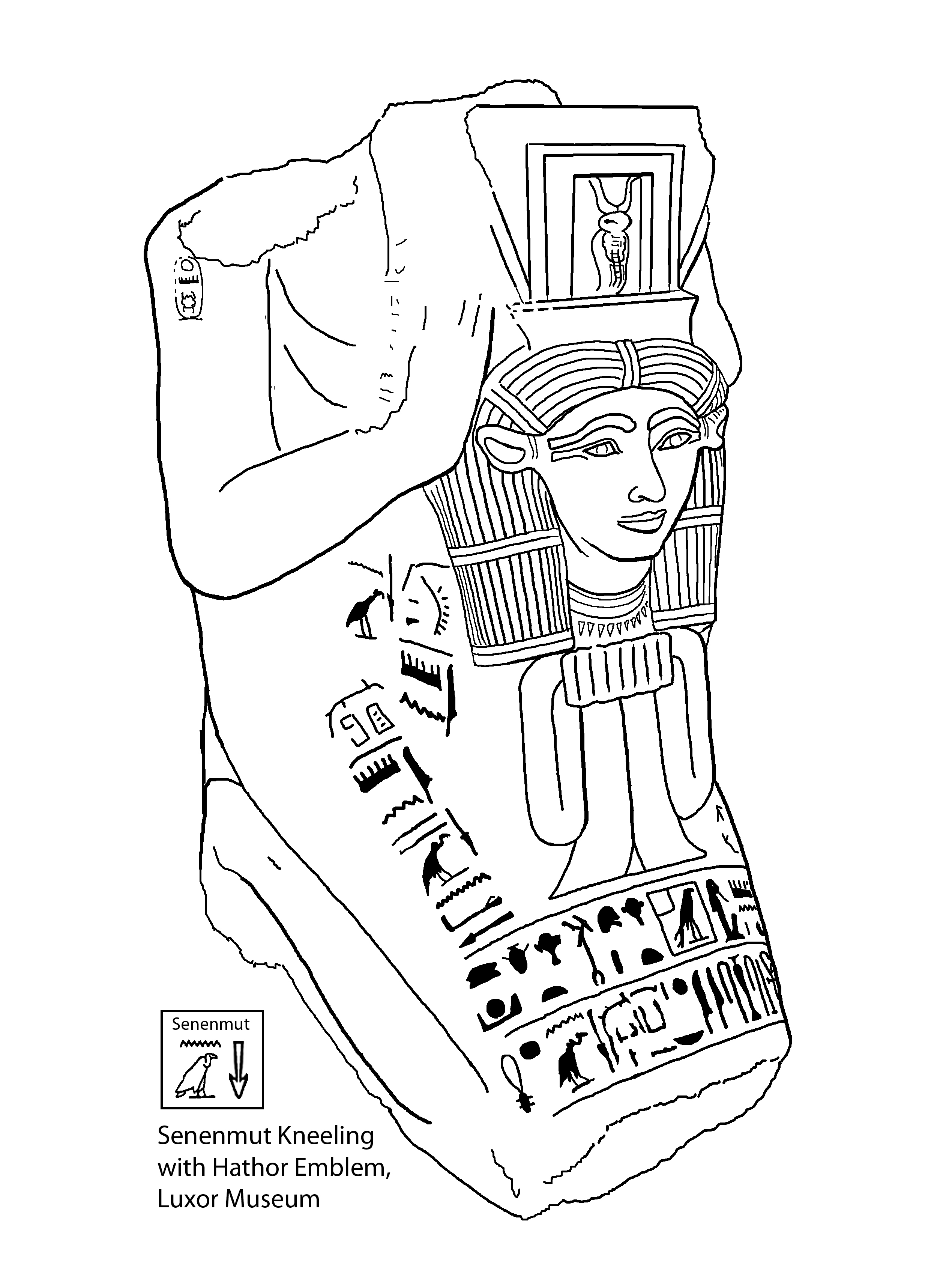

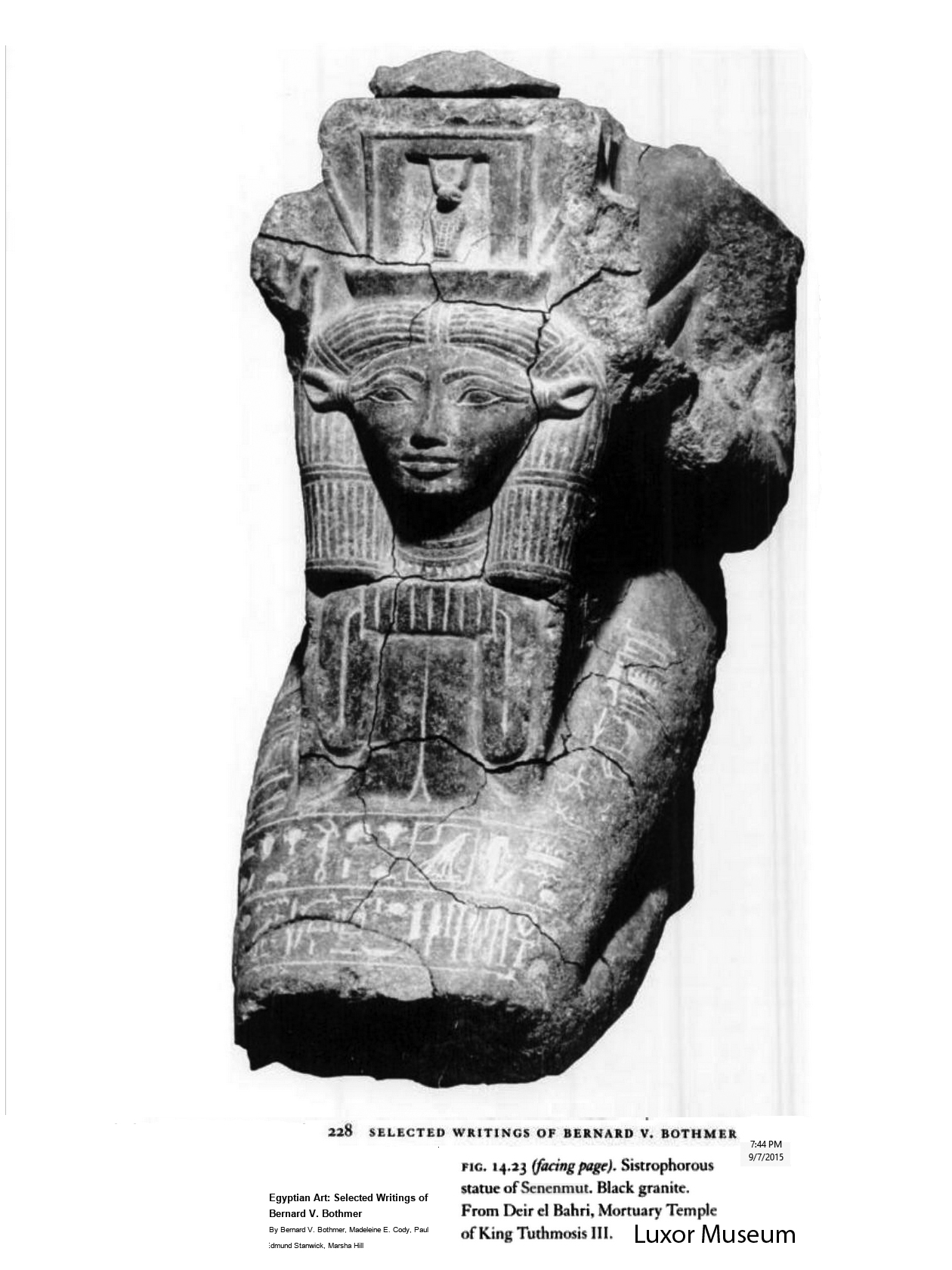

Four of Senenmut's statues are sistrophorus, a little one at the Met museum (22.5cm), one at the Munich museum (40.5cm), a huge one at the Cairo museum (155cm), and a headless but possessing an excellently detailed Hathor/Tyet (50cm) at the Luxor museum.

The right side of the back pillar of the Cairo statue says that Senenmut "supports Hathor, preeminent of Thebes, Mut, Lady (?) of Isheru. He causes her to appear and (52) displays her beauty on behalf of the life, prosperity, and health of the King of Upper and Lower Egypt, Maatkare, alive forever!" (Hatshepsut: from Queen to Pharaoh, pg. 300) The inscriptions also state that the statue "was a royal gift; second, that it was made specifically to be placed in the temple of the goddess Mut so that Senenmut could continue to share the bounty of her offerings." (Hatshepsut: from Queen to Pharaoh, pg.125) |

Senenmut Kneeling with Hathor Emblem

Senenmut Kneeling with Hathor Emblem Early 18th Dynasty, joint reign of Hatshepsut and Thutmose III (1479— 1458 B.C.E.) Gray granite or granodiorite, H. 50 cm (19 1/4 in.) Egyptian Department of Antiquities Magazine, Luxor Trace by JAL of a photo found from Seventy Years of Polish Archaeology in Egypt, Photo via _Egyptian Art: Selected Writings of Bernard V. Bothmer_, by Bernard V. Bothmer, Madeleine E. Cody, Paul Edmund Stanwick, and Marsha Hill |

|

"This superb but badly damaged statue of

Senenmut was discovered in 1963 at Deir el-

Bahri, in the ruins of the Djeser-Akhet temple.

Both the upper part (the head, neck, and top of

the back pillar) and the base are missing. The

quality of the workmanship is, however, excellent, as is particularly evident from the front.

The Hathor head and tayet knot are especially

well executed, and the hieroglyphic text imparts

a luxurious quality to the work, surrounding

the statue as if it were wrapping Senenmut in an

elaborately embroidered garment. That he is

actually wearing a simple, unadorned kilt is

revealed only in the side view, which also shows

torso with folds of fat. "The inscriptions inform us that the statue was dedicated to both "Amun-Re and Hathor, preeminent of Thebes, who resides in Kha- Akhet on behalf of life, prosperity, health, and favor every day for the ka of the Steward Senenmut, like Re.'"(Hatshepsut: from Queen to Pharaoh, pg. 126)

The Munich museum statue is inscribed with text on the right side of the sistrum which states " 'He supports the sistrum of Iunyt who resides in Armant, so that her place is elevated more than those of the (other) gods. He causes her to appear. He displays her beauty.' Armant (Iuny in Egyptian) is one of several locations in the greater Theban area sacred to the Egyptian war god Montu. At Armant, Iunyt was worshipped as consort to Montu and mother of their offspring Horus-Shu."(Hatshepsut: from Queen to Pharaoh, pg. 126) Senenmut was quite innovative. "On one of the statues of Senenmut with the princess's head, he had written "Images which I have made from the devising of my own heart and from my own labor; they have not been found in the writing of the ancestors." "Senenmut produced a sculptural corpus containing a notable number of creative 'firsts.' Some of these came to be so closely identified with Senenmut that they suffered (momentary) eclipse after the period of joint rule, but most became standards of the artistic repertoire." (Hatshepsut: from Queen to Pharaoh, pg. 117) "Senenmut's sistrophores are the earliest known examples of this statue type, which would become an extremely popular form for officials' expressions of devotion to a female divinity, particularly Hathor." (Hatshepsut: from Queen to Pharaoh, pg. 118) Thus he inspired Kaemwaset, who probably commissioned the same sculptor, based on the style:

( Museum website description: "Black granite statue inscribed for Kaiemwaset. The nobleman is represented as kneeling and proffering a large Hathor-sistrum. Kaiemwaset is dressed in a long skirt. The figure is inscribed on the right shoulder, the back pillar, the front, sides and upper front surface of the base, and on the sides of the mass of stone which connects the sistrum and chest. There is some red pigment preserved in the hieroglyphs on the front of the base. The figure bears the cartouche of Tuthmosis IV. Condition: The head, except for the parts of the wig, neck and beard, is missing. Large chips in the front, right side and rear of base. The left arm, left foot and left side of the base are mostly chipped away: the back pillar is only partially preserved. There are smaller chips in many places, and there is dried mud on much of the surface.

"Kaemwaset was connected with the temple of Amun-Re at Karnak in Thebes (modern-day Luxor). The inscription on this statue invokes that god, as well as the goddesses Mut and Nebethetepet. It would have enabled the deceased Kaemwaset to share in the daily temple offerings to the gods and to participate in the daily rites of resurrection.

"The royal name carved on Kaemwaset's upper right arm dates his statue to the reign of Thutmose IV. The rolls of flesh on his torso are an artistic convention indicating his prosperity. The object that he holds represents the head of the goddess Hathor resting on a protective Isis-knot. On her head is a miniature temple gateway flanked by two volutes. These forms suggest the sistrum, a musical rattle whose sound was beloved by Hathor and other goddesses. The cobra shown in the doorway and two others on the sides also evoke goddesses and their protection."

Despite the damages, I could make out the glyphs for Amun and Mut.

This example is particularly beautiful in the way the artist depicted Hathor and in subtle details, such as the subject's toes. I was able to read the accession number on Heidi Kontkanon's photo, and thus was able to learn more:

I was able to find three sources for this piece. One is in Italian, but with photos. One is is English, and by comparing two online sources, I've managed what may be the complete reference. And one is in French, but I could manage it okay. From Pernigotti's article, I was able to get the subject's name and one photo showing an interesting perspective from above. I hope it is "fair use" to share the following:

I found many more photos at the Institut Français d'Archéologie Orientale's website. I took one of those as the main guide for this tracing, but needed to refer to all of the photos to discern the close details:

Also, these authors give a more precise dating but disagree with Pernigotti: Josephson and Eldamaty also give clear copies of all the hieroglyphs, but I wasn't able to find direct translations. They may be tucked in a part of the book not accessible to online peeksies. I can only make out with my dabbling knowledge, the standard "An offering that the king gives"...something... "Lord Amun-Ra"...something..."Two lands"..."All the Gods of?"..."Waset"

The cartouche below Hathor's face says "Great Royal Wife Mutemwia". The view from the front of the barque reveals the cartouche of "NebMaatRa" within the Hathor sistrum. So he likely had this piece commissioned when he was king, as he did so many other magnificent pieces. It's an amazing sculpture, a play on words, for Amenhotep III's mother's name "Mutemwia" means 'Mut is in the barque', and that's how she is depicted. It's too bad her torso and head are lost, but we can see that she is enthroned, holding an ankh and embraced by Mut in the form of a vulture:

I like the way Hathor's hair follows the slant of the boat on the side which faces Mutemwia:

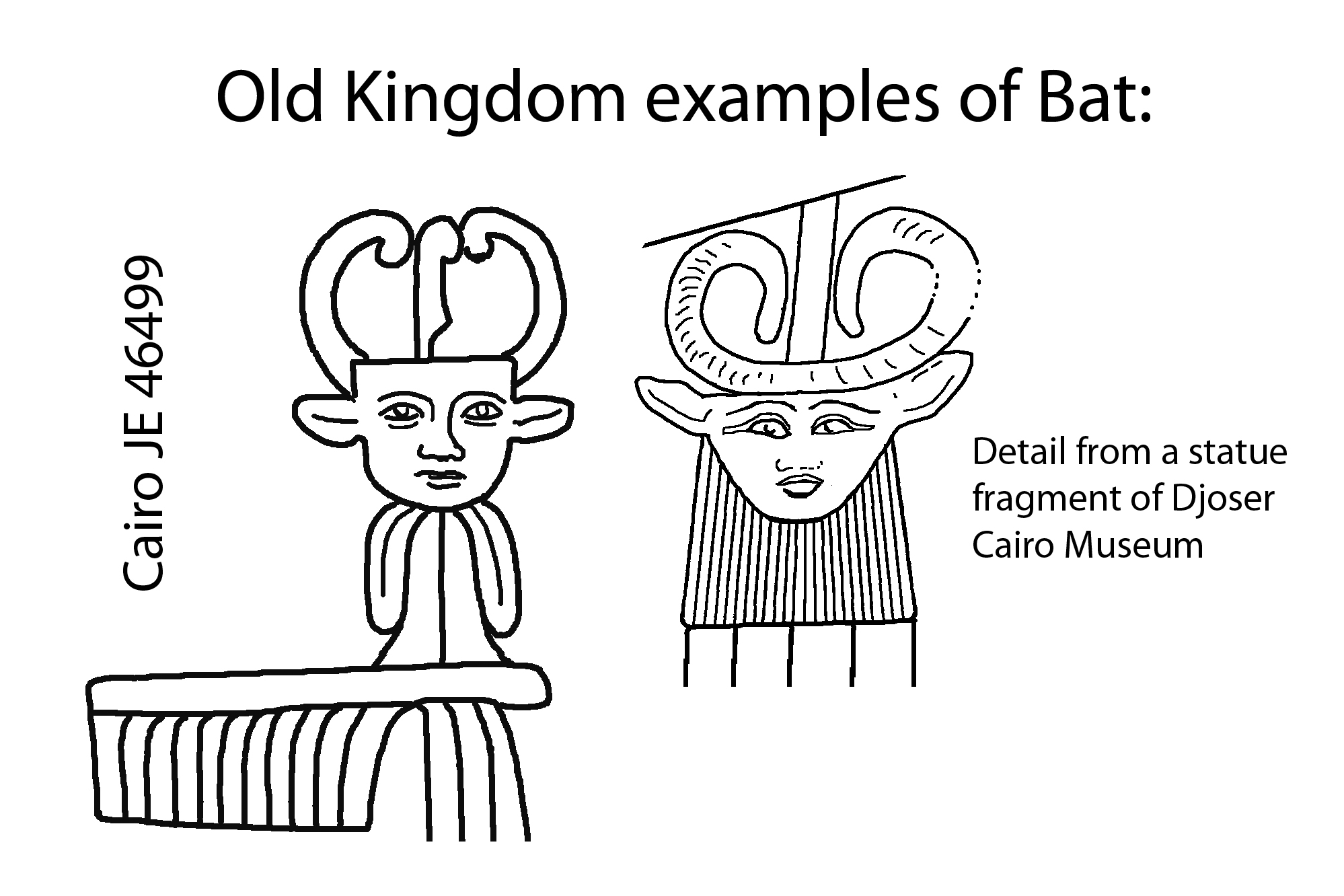

"Bat was an early cow goddess whose name means 'female spirit' or 'female power' and who appears to have been an important deity of the late predynastic and early historical times." She was the deity of the 7th Upper Egyptian Nome, which is called "Mansion of the Sistrum" and is situated at "the Nile’s return to its south-north direction around Nag Hammadi", otherwise known as the "region of Hiw". The region of Dendara, whose deity is Hathor, neighbors it. Bat has horns as does Hathor, but her horns curve inward, rather than outwards. This distinction from Hathor wasn't enough to keep her from getting absorbed into the iconography of Hathor, by the Middle Kingdom, yet as we've seen, her characteristics continue onwards. Those lyre-shaped curves are kept in illustrations of the sistrum.(Sources: _The Complete Gods and Goddesses of Ancient Egypt_, by Richard Wilkinson and _The Routledge Dictionary of Egyptian Gods and Goddesses_, by George Hart) There's an example of Bat/Hathor from the Third Dynasty:

"This stamp, in the form of an oval topped by two feather plumes, bears the inscription 'Hathor in Imu.' Imu, known today as Kom el Hism, is located in the west central delta. The site is poorly preserved, but textual sources indicate that the goddess Hathor was the principle deity of the town. This bronze stamp may have been employed to mark the bricks used in that temple." ( Ancient Egypt: Treasures from the Collections of the Oriental Institute University of Chicago, by Emily Teeter, (Oriental Institute Press, 2003), page 78)

I was so curious to learn more, but unfortunately, I wasn't able to turn up much. I did learn Imu's history goes back further than the New Kingdom. Senwosret I of the Middle Kingdom "founded a temple to SEKHMET-Hathor at IMU, now called Kom el-Hisn, the Mound of the Fort, in the Delta. The temple was rectangular and contained a bark chapel and pillars. (Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt, by Margaret Bunson, (Facts on File, Inc., 2003) page 363)

I also found a reference to Hathor as Mistress of Imu from the Old Kingdom.

Pepi II, the last 6th Dynasty pharaoh, wrote a letter to a Harkhuf, who made a profitable journey to Nubia:

"...thou has descended in safety from Yam with the army which was with thee. Thou hast said [in] this thy letter that thou hast brought all great and beautiful gifts which Hathor, mistress of Imu, hath given to the ka of the King of Upper and Lower Egypt Neferkare ( = the prenomen of Pepy II)" (Daily Life of the Nubians, by Robert Steven Bianchi (Greenwood Press 2004), page 49)

Miriam Lichtheim's translation of New Kingdom literature has one reference to Imu, a footnote to Imu being a "word play on im3, 'gracious'"

(Ancient Egyptian Literature: Volume II: The New Kingdom,

by Miriam Lichtheim, (University of California Press 2006), page 199)

While searching in that book, I did a general search for "Hathor", and turned up something quite fascinating. Paheri's 18th Dynasty tomb at El-Kab has a relatively lengthy prayer for offerings. Lichtheim describes it, the "back wall of the main hall of his tomb was given the shape of a round-topped stela with a niche in its center. The niche was filled by three seated statues, and the surface of the stela was inscribed in horizontal lines with a text that begins in the rounded top and continues on the right and left sides of the niche. This is a mortuary text consisting of four parts: (1) the traditional prayer for offerings..." (page 16)

With this information, I could take to the web and hunt photos. Bruce Allardice has the most legible photo, while Osirisnet has a line image with the glyphs). Between the two, I was able to make out the hieroglyphs:

|

(From right to left) Hathor, mistress of the desert (foreign lands) Strong of heart among the gods; (And) Ptah-Sokar, lord of Shetyt (the Secret Chamber)

I've assembled a PDF of these findings.

Hathor at Deir el Bahri, traced from a photo by Kyera Giannini As I traced, I noticed some barely noticeable faint lines which gave clue to things that had been erased in antiquity: two images of Hatshepsut had been scratched out. A similar Hathor cow also in Deir el Bahri has a less damaged scene, revealing Hatshepsut standing in front of the goddess and also being suckled:

I took a trace of the suckling scene:

"The Hathor chapel of the Deir el-Bahari temple of Hatshepsut is the earliest known structure dedicated to that goddess on the west bank.12 Depicted in the form of a cow, she is titled Hathor of Dendera, Chieftainess of Thebes. As the protective and nourishing mother, she is shown licking the queen, as the cow does her calf.13 Cattle references are prominent in the accompanying texts, where Hathor is referred to as the Tjenenet cow and Apis is the Tjenen bull, "who engendered the heifers."14 Anubis is also cited here as the 'Lord of the Horned Ones, who resides in the land of the heifer.'15 The birth of Horus in the marshes is the underlying theme of these scenes. The goddess kisses the queen, 'as I did for Horus in the nest at Chemmis.' Hatshepsut, the child of the divine cow, is 'my Horus of Gold.'16

"Suckled by the divine cow, Hatshepsut receives the gifts of life and strength as well as the power of the transfigured Akhu.17"

Lana Troy, "Religion and Cult during the Time of Thutmose III", Thutmose III: A New Biography,

edited by Eric H. Cline and David B. O'Connor, (University of Michigan 2006), page 125

I wasn't able to learn much more about it, other than a snippet reference from a book partly authored by Werner Forman in 1962, in which I learned Tanefer was "the third prophet of Amon". Taking the search further, I learned from an 1895 book by Karl Baedeker that the "Gizeh museum" has a "Sarcophagus of Tanefer, with ten titles [], among which is that of 'steward of the herds in the domain of the sun-god', recalling the Homeric 'cattle of Helios'." Baedeker also refers to the "Sarcophagus of Ra-men-kheper, son of Tanefer, whom he succeeded as third prophet of Ammon." (page 123) Notice, too, that Tanefer has a sash tied around his head, could this again be the tjetsen which assures safe passage through the underworld?

The first bowl is at the Met Museum. I've chosen to trace the photo of this piece with the flowers to better illustrate how it would have appeared to those using it.

"The interesting bronze *flower bowl of figure 121, found with two others in the forecourt of the tomb of the Vizier Rekhmi-Re, was apparently designed as a votive offering to the goddess Hat-Hor and has as its centerpiece a little bronze figure of the Hat-Hor cow crowned with the solar disk and double plume and raised above the bottom of the bowl on a small metal bridge. When the bowl is partly filled with water and with flowers the animal appears to be standing in the midst of a marshy thicket, reminiscent of the thickets of Chemmis, where Hathor is reported to have nursed the infant Horus..." (William C. Hayes, _The Scepter of Egypt_ Part II, (Metropolitan Museum Press 1959), pages 205-206)

(Horus??? Or Ihy???) Usually Hathor is said to be mother of Ihy, while Isis(Aset) is said to be mother of Horus.

The other bowl is of faience and a bit smaller:

Eton College website description:

The museum description is: "Limestone stela of Amenmose: there is a large, Hathor-headed sistrum in the centre of this round-topped stela flanked by lotus flowers around the head. In the lower right-hand corner the sculptor of Amun, Amenmose, stands in adoration holding a brazier. On the left the lady Baketseth stands with her arms raised in worship. There are several gouges and areas of wear on the surface of the stela and the edges are damaged in places. The wear on the face of the Seth animal may not necessarily be intentional." The many gouges and worn spots made tracing and translating difficult. But I gave it my best shot: Upper Left, very uncertain. After a fairly clear Hathor glyph, the next two are quite worn, and my choices are practically guesses. The third glyph may even be 'ka' arms, rather than the 'p' square. I'm sure the next is a phrase, but I haven't as yet come across its like. (I have another highly recommended hieroglyph book on order!) The ending glyph may either be the 'dua' (adoring) or the 'hai' (rejoicing) glyph. The museum tracer chose the rejoicing glyph, but it looked more to me like the adoring glyph.

Lower left:

Lower Right:

I found it fascinating and wanted to learn more. Roberts explains

"Plate 40 shows Seti kneeling devoutly before Hathor, 'the female Hawk', who appears in the form of a human-headed Ba-bird. Between the king and the goddess are inscribed the words

Roberts explains, "the Ba represents above all the capacity to appear as a dynamic, living presence and emanate power affecting others." (page 52)

How often has Hathor been depicted as a Ba-bird? Could there be any other meaning beyond what she gives there?

I've found two examples of people who are depicted in an attitude of devotion before a ba-bird, each of these bearing a face resembling the person.

Inherkhau's tomb has one example:

Kent Weeks explains:

Osirisnet.net describes this: "Chamber G, North wall, upper register. The whole register is represented in 4 photographs. Inherkhau raises his arms in adoration before his Ba which stands on his tomb."

The Osirisnet author clearly states this is his own Ba that he is facing and giving the Dua(adoration) gesture.

Another scene of Ba-devotion occurs in the Book of the Dead of Tentameniy:

Alison Roberts describes this: "Vignette from chapter 26 of the Book of the Dead, equaled with the ninth hour of the night. A chapter of the heart, it begins with the words 'May my heart be mine in the House of Hearts'/ Holding her heart, the lady Taameniu kneels before her Ba, which wears a Djed symbol of 'stability', symbolizing her stable existence..." (page 153)

Wearing the Djed expresses her Ba's eternal nature.

Returning to the tomb of Inherkhau, Kent Weeks describes the adjacent scene, "At left, a second scene shows the deceased before Ptah, the god of craftsmen and therefore one greatly praised in Dayr al-Madina. The text that follows at left is a copy of Book of the Dead chapter 42, a list of body parts and the deities associated with them. “My hair is Nun,” one of the rectangles proclaims, “My face is Ra; my eyes are Hathor; my ears are Wepwawet; my nose is She who presides over her lotus leaf.” (Illustrated Guide to Luxor)

This declarative statement type of Heka is frequent in the Book of the Dead texts. The association is of a possessive/transformative nature, "my eyes ARE Hathor".

Could Seti I be adoring his ba, which has become as Hathor? Seti's temple was begun under his rule, and then continued after under his son Ramesses II's rule. One of its many chapels is dedicated "to the deified Sethos I", (Richard Wilkinson, _The Complete Temples of Ancient Egypt_, page 147) ("Sethos" is the Greek way to refer to Seti).

As Seti I was considered to be deified, this makes my hypothesis more possible. At the very least, perhaps Seti's at least acknowledging Hathor as the maker of his Ba? With this creative possibility, She could thereby be able to give "charm and attraction", enabling Seti to better navigate the difficulties of the Duat.

But as I examine the scene in Seti's Chapel of Nefertem, I think there is a more simple explanation.

Seti is giving adoration to (in order) Nefertem, Ptah, Shu, "Horus who is over his papyrus column", Isis, Nekhbet and at the end, Seti is again depicted kneeling and offering two bowls of (wine? water?) to Hathor who is depicted as a falcon with the head of a woman.

This depiction could simply refer to the early cow goddess Bat, whom Hathor later subsumed. As Bat's name means

"female spirit", this is more likely what Seti's image is referring to. Let's examine again how Bat was illustrated during the third and fourth Dynasties:

Or could the image be referencing both of these concepts?

Thumbing through this book, I was pleased to find a scene with both Hathor and Ptah. So I wasted no time in scanning it. The book already had its own trace, but even if it had scanned better, I still wanted to do my own. Martin thinks Raia is being shown as blind, but I think the shut eyes merely indicates the musician is so into the music, they shut their eyes. Also, if Raia's song was a prayer, his eyes could be closed to better focus on the spiritual world?

Ptah grasps the Was scepter, while Hathor, named "mistress of the sycamore", offers the menat necklace with one hand, and holds an ankh with the other. Ptah is named "Lord of ma'at" in the glyphs directly above the flower offering. I don't know what the glyphs say above that, though.

Coffin Texts Spell 532 reveals: "'I have received my spinal cord through Ptah-Sokar, my mother has given me her hidden power.'"(_The Quick And The Dead: Biomedical Theory In Ancient Egypt__, page 188) Could that mother have been understood to be Hathor? "Here we will but mention in passing the Egyptians' paramount cow-mother goddess Hathor. As 'Lady of Life', she was responsible for giving life to all creatures (LÄ II 1025 and notes 23-24)."(_TQatD_, page 27)

I admit the artist of this stela wasn't the best. Hathor's ears are too high, the pharaoh's eyes are out of place, and the glyphs aren't very clear. One photographer thought the cartouche could be saying "Amenhotep", while the other ventured "Ramesses II". "Amen" can plainly be seen. But more of the glyphs resemble those of Ramesses, so I'm going with that.

Perhaps this piece wasn't commissioned by the pharaoh, who would have employed the best, but by someone less royal, who simply wanted to bless the pharaoh, and took whoever was available.

Hathor presents palm branches to the pharaoh, which means "length of time" and "years", thereby ensuring he will have a long reign. The figure at the bottom of the branches is supposed to be a tadpole, meaning "100,000". Also, she offers him the ankh, representing her endowing the pharaoh with life.

|

|

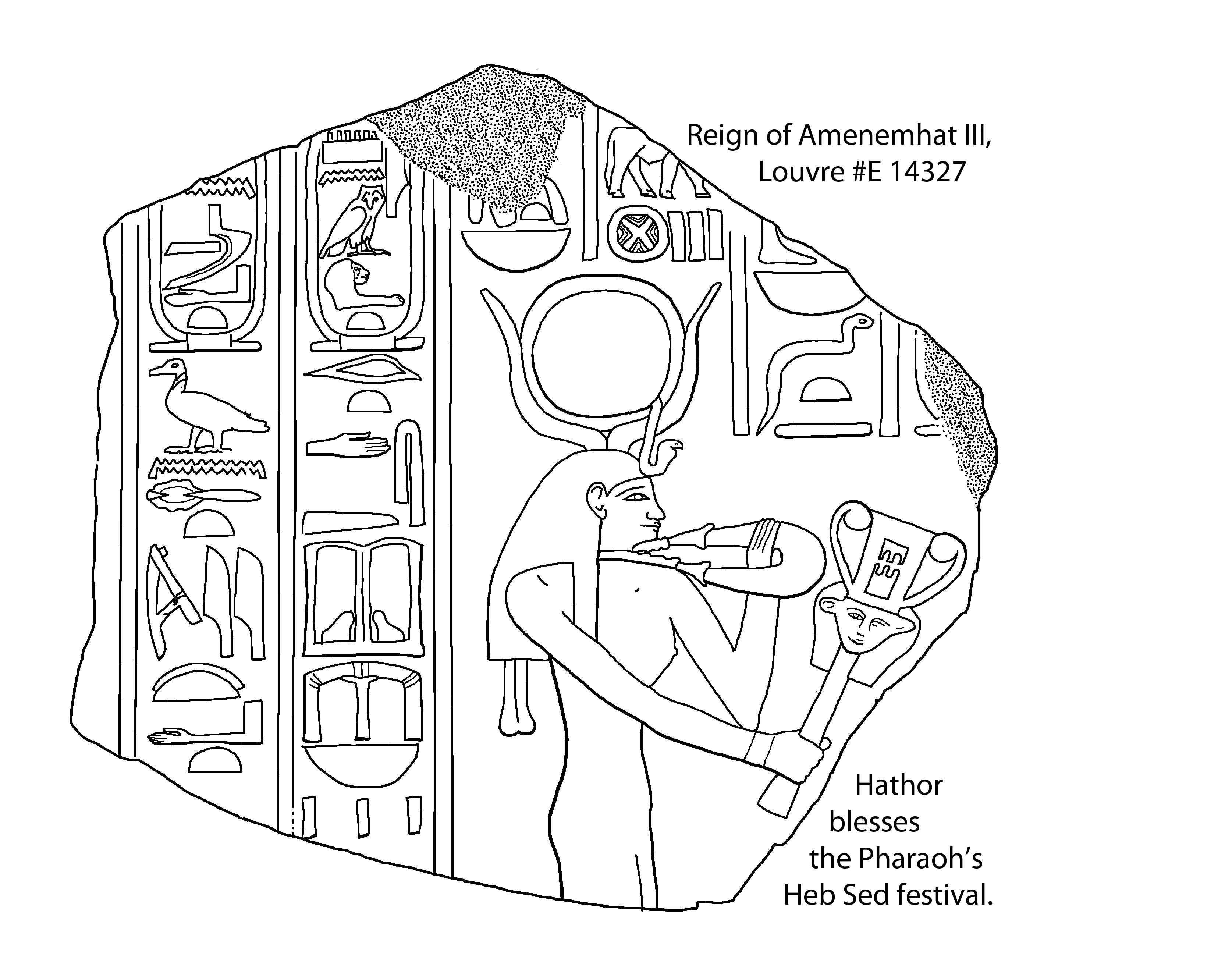

My trace from a photo in _Ancient Egypt Transformed: The Middle Kingdom_, page 103: Relief of the Goddess Hathor Limestone, Height 63 cm, (24 in) Twelfth Dynasty, reign of Amenemhat III (ca. 1859-1813 BCE) Lisht North; Institut Français d'Archéologie Oriental excavations, 1894-96 Louvre #E 14327 |

|

"The inscriptions commemmorate the rites that took place on the occasion of King Amenemhat III's Sed festival, or thirty years jubilee, which was commemmorated or marked at the tomb of his ancestor Amenemhat I at Lisht North. Hathor offers her blessings in return for the king's devotion to her cult at Tepihu (modern Atfih), located 19 kilometers south of Lisht, on the east bank of the Nile. The inscription provides rare evidence that a temple was erected at that site in the Middle Kingdom. The presentation of a menat also appears on another stela in this volume (cat 193), in which the detailed relief exhibits the same suppleness and the object is decorated with a multitude of individually rendered beads. The two symbols on this relief, the musical sistrum and the menat, were intended to procure joy and rebirth for Amenemhat III, purposes that account for their association with goddesses, such as Hathor, who were related to the life cycle and birth." (Elizabeth Delange, curator of the Egyptian department at the Louvre, _Ancient Egypt Transformed: The Middle Kingdom_, page 103)

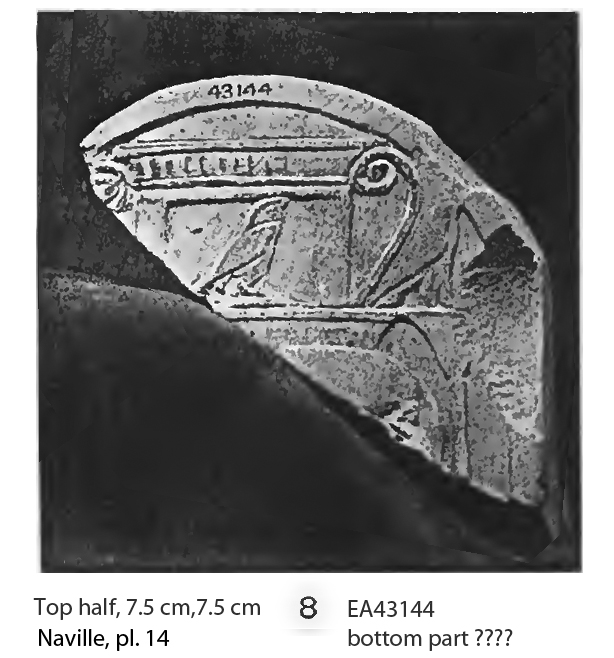

I tried to track down where this appealing little plaque has gotten to, with only partial luck. I found the location of part of it. The top half is at the British Museum, "not on display", and given the number EA43144. Naville has a photo of this top half, showing the museum number:

The Met museum has this tiny plaque, also from the 18th Dynasty, on display:

|