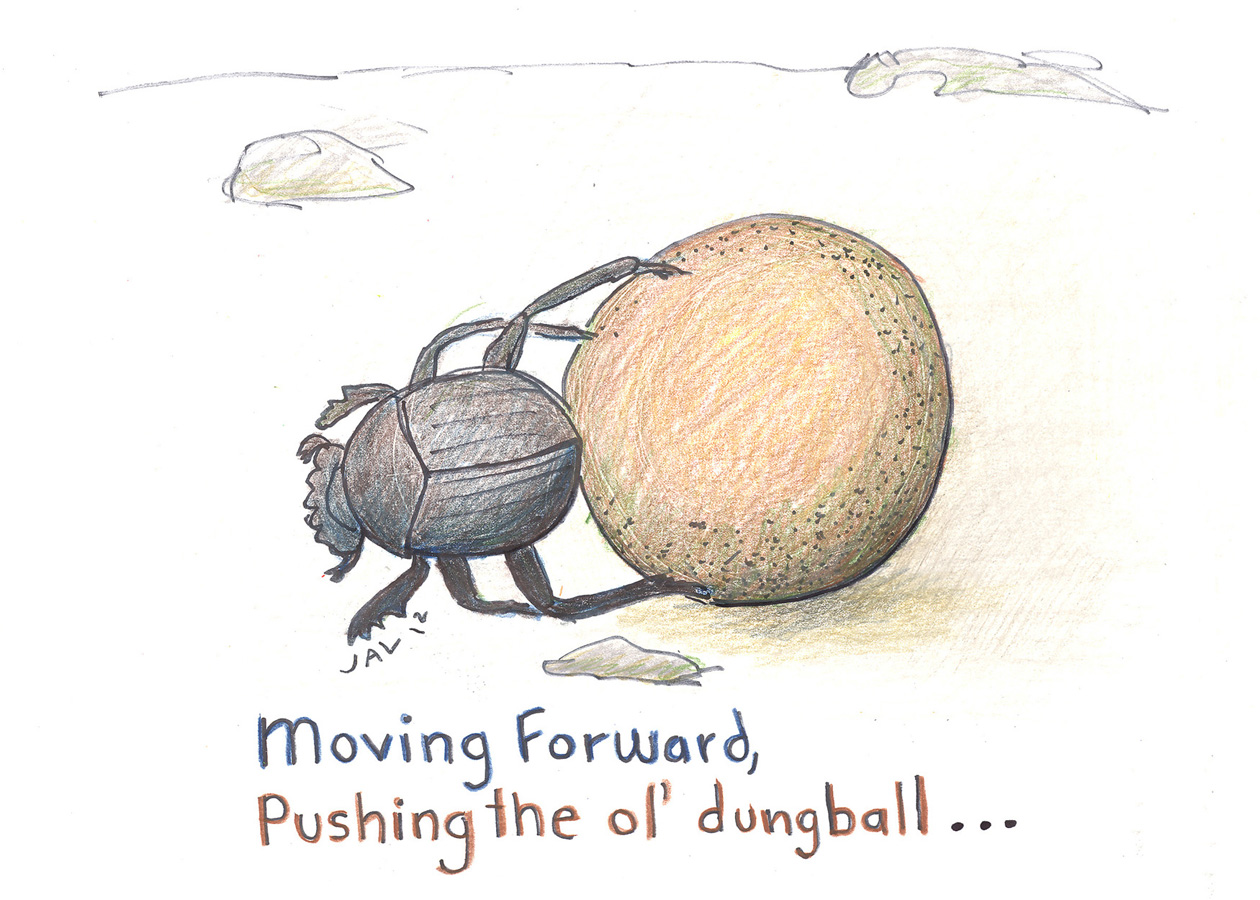

Moving Forward,

Pushing the ol' dungball...

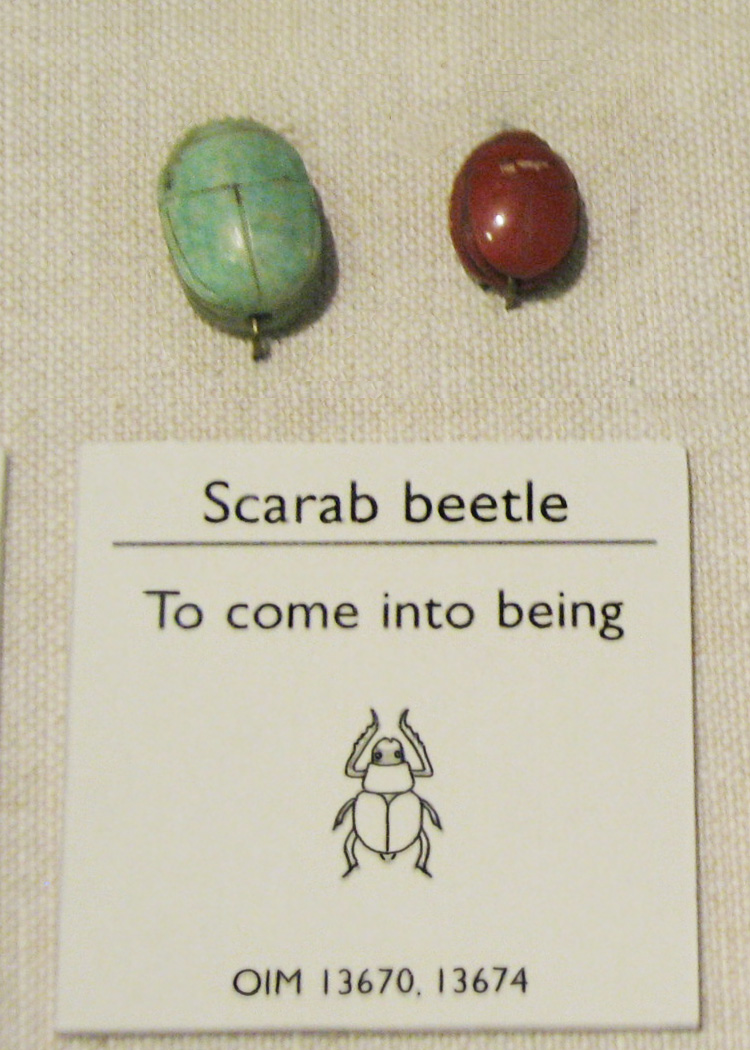

| Dung beetles such as the "roller" above live in warm climates. They form nearly spherical balls of dung, which they roll over sometimes considerable distances to their burrows. The dung is a store of food, from which they feed. "Rolling is usually accomplished by the beetle standing on its front legs and then pushing and manoeuvring the ball with its hind legs"(1) So essentially, they are walking BACKWARDS as they move FORWARD to their destination. "Dung beetles play a remarkable role in agriculture. By burying and consuming dung, they improve nutrient recycling and soil[7] structure. They also protect livestock, such as cattle, by removing the dung which, if left, could provide habitat for pests such as flies. Therefore, many countries have introduced the creature for the benefit of animal husbandry. In developing countries, the beetle is especially important as an adjunct for improving standards of hygiene. The American Institute of Biological Sciences reports that dung beetles save the United States cattle industry an estimated US$380 million annually through burying above-ground livestock faeces.[8]"(2) The ancient Egyptians gave great important to this beetle in their mythology. The round ball of dung was likened to the sun as it rolls across the sky. "Because the female scarab beetle also lays her eggs in a similar dung-ball, from which the young eventually emerge - as though spontaneously - the reproductive biology of the insect may underlie the name of the god, as Khepri suggests the Egyptian verb kheper, meaning 'to develop' or 'to come into being'. As a result, Khepri, 'he who comes into being', was the god of the dawn of creation and was sometimes linked with the creator Atum as Atum-Khepri, though his identity as the morning sun remained primary and his essential mythological role was that of raising the sun from the horizon in the eternal cycle of solar rebirth."(3)  Scarab Beetle "To Come into Being" (aka 'kheper' or 'xeper') Oriental Institute Museum 13670, 13674 1. Wilkinson, Richard, Egyptian Scarabs, Shire Egyptology, 2008, page 8 |